The Bench

It is 25 years since New Labour won its landslide victory on May 1, 1997 an event I watched on TV with friends in an attic flat in Estrela, in Lisbon towards the end of a decade of self-imposed exile from Thatcherism. We were delirious with wine and the spectacle of the order changing at last: a long and heavy 18 years. The joyful bells of the nearby Basilica, which pealed regularly across the freguesia, became attached in memory to that night alone.

Just before I left England, I had been teaching school students who wore gloves in class because the windows didn’t fit properly. When I returned, in early 2001, the mantra of the new government was education, education, education. I got a job in a FE college managing an ESOL department and soon came to realise that this translated in practice to audit, audit, audit. There was a new vocabulary to acquire: Individual Learning Plans, the new Curriculum and Standards, competence-based frameworks, market segmentation, stakeholders, the Knowledge Society, the High Skills Economy. Endless mapping exercises were conducted each of which left the teachers persuaded they were not trusted to do their jobs. Still, there was money for conferences with catering, something teachers were not used to, high production value materials to support the new learning infrastructure as it was called, and funding sufficient for the young adult provision to treble.

A year after September 11, the elaborate and frenzied exercise of enrolments took place, with queues forming around the block and the corridors echoing with the raised voices of sweltering women in burkas and hijab, some with children, and exhausted looking men who had come straight from working a restaurant shift to have their level of English assessed and sign up for an English class if they were lucky. Demand for places far exceeded supply even with the investment in Skills for Life, as it was called.

This was when I met Tareq. He walked with a limp and had come alone. He was clean-shaven and wearing a cotton shirt with the sleeves rolled up revealing bony forearms. When I assessed him, he seemed to have flashes of understanding and some fluency but then would close down completely. His writing resembled a cardiac trace. He had soft hazel eyes which he trained on my face. He smiled too much. Then, even more unnervingly, he began to laugh, his face wrinkling, his gaze eventually resting on the ceiling, as if an internal story had reached its punch line. Just as unexpectedly, he fell silent. I made a note to follow him up, and in the meantime assessed him as a near beginner and moved on.

As it turned out, the following week he arrived in my class. I learned from the Student Services team that he had fallen or jumped from a fifth-floor window and that he was being looked after by his younger brother, Alan, who shouldered the responsibility, but had numerous difficulties of his own. They lived in rooms together a fair distance from the college. Tareq had been studying engineering at the University of Kabul until it closed and had left Afghanistan some years before, after the rise of the Taliban.

When he responded to the other students’ with inexplicable mirth, it was obvious that something had to be done. It was all very well to laugh at a joke that no-one else could hear, but another thing to seemingly ridicule others’ efforts with the tricky new language. With Tareq’s consent, I explained the situation to the class, who behaved with impeccable tact. Hawa, a nurse in Somalia, who had the gentlest face and humour and lived in a local hostel called Hope Town, was the first to extend a tentative hand of friendship. Abbas, thin and swamped in an oversize print shirt, who had come from Somalia by way of a refugee camp in Ethiopia, who took months to speak, but weeks to learn how to use a computer and write his story, was next. The rest of the group, which included a cab driver, a University graduate from Chittagong, three Somali mothers and a mother to be, a part-time security guard, a teenage boy who worked in Perfect Fried Chicken, a girl of similar age from Mogadishu, and a number of Job Seekers, eventually expressed their good will to the aloof young man.

By December the class were chatting away and had organised a Christmas party. Through their writing and anecdotes, I came to know more about their quirks and circumstances. Salma, the bossiest of the group, seven months pregnant when she enrolled, had her baby and returned to class a month later. The student with the economics degree got married and invited us all to the wedding. Some were called away to do Job Seekers’ courses. Tareq remained a mystery, even to the Pashto speaking Counsellor, who concluded that his injuries would not prevent him from learning, but that the Afghani boys were a wild bunch, adrift in the UK away from their families. Tareq was sometimes late for class; apart from that he fit in well enough, though the others were slow to partner him.

As winter deepened, the prospect of war in Iraq loomed and in February I joined the mass demonstration, as did others from the college. The soundtrack was whistles, the driving rhythm of the batucada, and the dirge like drone of a group of women who called themselves Voices from the Wilderness. In homage to the US President’s incomplete grasp of his own language, the friend I was with carried a banner that read:

Bush is evil personificated

His regime must be resistified

In the evening a man in a white boiler suit with Weapons Inspector painted on the back, warmed up the Non Violent Direct Action crowd: ‘Is everybody happy? Are you feeling nervous?’ In Piccadilly Circus, the university students chanted: Oh sit down, oh sit down, sit down next to me. Some did and were dragged away by the police. Others like me left willingly. Despite the Mall being a sea of placards all saying, ‘No’, it wasn’t enough to stop the Government preparing for war.

The adult ESOL students mostly kept their counsel, I imagine reserving their honest views for the mosque. On the day of the invasion, however, the reality struck home and many students walked out of the college at lunchtime and joined the march to Parliament Fields, from Altab Ali Park in Whitechapel, named after the textile worker murdered by racists on his way home on the eve of the local elections in 1978.

I went with two young women from the class, just back from the compulsory Job Seekers’ course, who viewed the day as an adventure. Girls in maroon shalwa kameez from the local girls’ school gathered with their teachers in the park and set off in their sling backs, clutching handbags, chanting ‘Bush, Bush, we know you; Daddy was a killer too’ and ‘Who let the bombs out? Bush, Bush and Blair!’ Hours later as we passed under the bridge at Embankment their voices echoed: ‘We are not in shock; we are not in awe. What are we? Angry!’ The London Eye glinted in the late afternoon sun.

Shortly after that day, the students heard that another class was going to Parliament and they wanted to go too, so I wrote to the aide of the local MP giving details of numbers and the visit was confirmed. Meanwhile, I made materials on how laws are passed and showed the students the website. They came to know more about the system than the average person, and so did I. They were intrigued. They joked about having tea with Tony Blair. None of them had met their MP. I told them about Emily Wilding Davis hiding in the broom cupboard of the Palace so she could give this as her address in the census, and how she threw herself in front of the king’s horse so women would one day be able to vote. They told me about noble martyrs from their country, Tareq offering the name of Meena, an Afghan freedom fighter, a teacher, shot by the KGB. ‘Women are like lion asleep,’ he giggled.

The day came. I made sure the older men kept an eye on Tareq. The women had dressed up. In the tube train, the teacher of the other class walked up and down the carriage in a crisp cotton jacket, as if he were the emcee and London itself his party. I tried to relax.

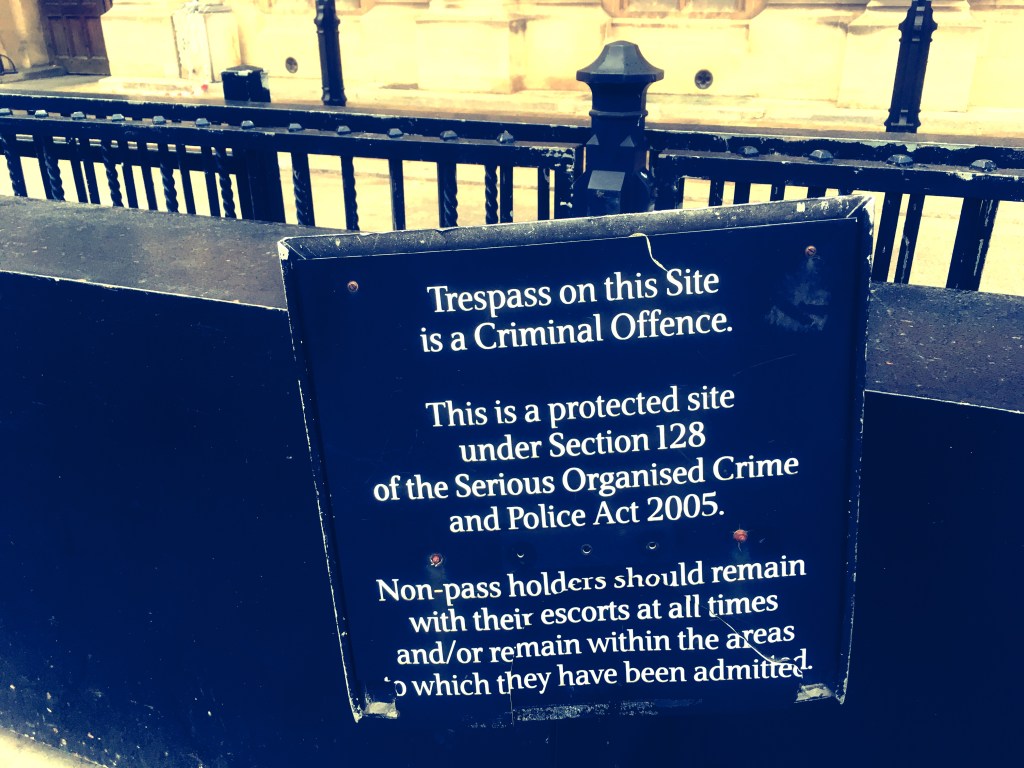

When we arrived at Parliament Square the students noted with surprise the handmade posters of the Brian Haws Peace Camp across the road. We made our way through the security gate. Then the MP appeared in a button-down with perpendicular striped tie. My warm greeting was interrupted by the words: ‘Who are these people? How many are there?’ I stood speechless for a moment and then reminded him of the arrangement. ‘I was expecting one group; you can’t just go adding numbers willy nilly,’ he said. ‘We only have time for one group.’ My worry had been that the students might not follow the tour guide’s English, not that we might be turned away unceremoniously. I felt both cold and sweaty and rummaged around for the email which luckily I’d stuffed into my bag at the last minute and passed it to him. He scanned it, blamed his aide and attempted a smile which he gave up halfway. ‘We’ll have to do this quickly’, he said.

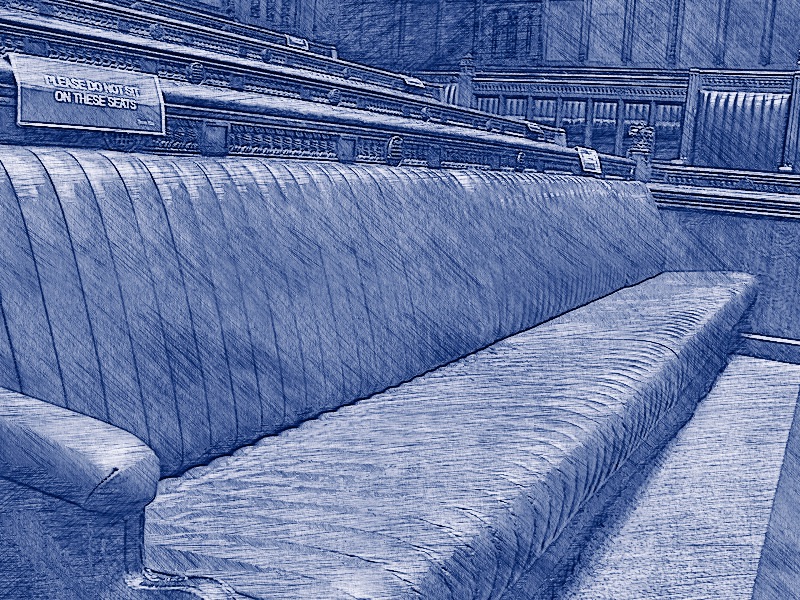

To my shame, I tried to usher the group through at a brisk pace. But Tareq’s limp slowed us down and the students were determined to savour the experience. I also had to explain the tour guide’s commentary to them. We made our way to the Central Lobby and stood for a moment at the centre of the Parliamentary compass. In the red room as the students called it, we were shown the woolsack – an economy built on livestock was familiar to them – and the Throne. Then we tripped into the Commons Chamber, through the Churchill arch, built using stone that survived the incendiary bombing of Parliament during the Blitz. To have one’s seat of government destroyed, this was also something they knew all too well. The MP tended to the other group, and a guide told us about the arrangement of the benches, the Government to the right of the speaker, the Opposition to the left. ‘Tony Blair sits there,’ she said and then told us about the Divisional bell, and the surprising fact that members had eight minutes from that point to reach the Chamber: ‘The ayes to the right, the noes to the left’.

While I was imagining the nation’s politicians re-entering the Chamber in a country dancing manoeuvre, there was a scuffle behind me. From nowhere, two uniformed guards appeared, causing the student from the Job Seekers programme to recoil in fear beside me. But it was ok. The guards weren’t armed; no-one was hurt. Tareq was making himself comfortable on Tony Blair’s place on the bench, but faced with the guards, paled visibly. ‘There is a notice’, the angered tour guide said.

After that, it was a relief to move into the old Westminster Hall, with its timbered roof and hammer-beams rising from the backs of carved angels, a wide open space. We all had tea in the restaurant and went home. The class soon forgot about the incident although jokes at the MPs expense circulated in the staff workroom for a while. The students prepared for their speaking exam. I don’t remember much about the rest of that year. Tareq started missing classes. He began to look dishevelled, stopped shaving and complained about the walk from his accommodation to the college. He was distracted when he did appear; then he stopped coming altogether. I called his number several times but got no reply. Before college broke up for the summer, I ran into his brother in the corridor and asked after him. Alan looked tired and drawn; he had got a cleaning job at Canary Wharf and was just about managing to keep up with his own classes. He told me with sadness that he couldn’t look after his brother anymore. He said that Tareq would leave the UK and go to Pakistan, where their mother, a widow, and the rest of the family now lived. Maybe Tareq would get married. Judging from his recent erratic behaviour, I couldn’t see him travelling without his brother. I didn’t know how he would fly back to his mother’s arms alone, and I never saw him again.

Coda

Last month, to mark 25-years since the 1997 election, a day conference was held by the Mile End Institute in Coram Fields where Tessa Jowell had launched the new government’s Sure Start programme in 1998. Opinion was divided about the overall Legacy, but amicably exchanged and a buffet made it feel like a large family party. Will Hutton drew attention to what had been left off the table, a critique of capitalism, arguing that Thatcher had made it her business to shift public opinion, but in key ways, New Labour did not. He spoke of an unstable settlement that blew up in 2007/8, with London at the epicentre of the crisis.

My time at the college spanned the period that began with the new policies and investment and finished with the looming financial crisis in 2007, voluntary redundancy and an end to free English classes for asylum seekers. I don’t know what the members of the class did next, though I did come across Abbas after I left the college, in a porter’s uniform with a patient at the Royal London. Every political era leaves a feeling tone and vignettes that stand apart like witnesses. I think of that kind and resilient group and the boy that wanted to be an engineer, the refugee who fell.