Trail: I

I approached Swedenborg House in Bloomsbury, where the event was taking place, with a familiar gnawing anxiety, but once inside and warmly greeted, I settled into an unexpected ease, the effect of a wooden floor under my feet, oak panelling, and a sturdy leather-backed chair. The Neo-classical meeting room was skylit at first, but twilight soon fell, the groups of friends sat down and the talks began. Welcome to XR Writers Rebel. By the time the last of the speakers addressed us, her features were indistinct in the shadows. In a calm voice which also carried a sense of urgency, she began a dispassionate argument for a more sophisticated paper recycling system, citing a work by Mandy Haggith entitled, Paper Trails, the name the group adopted for the campaign, which I made a note to read.

For every 25 books produced a tree felled. 75-90% of books printed on virgin paper. Paper plantations existing at the expense of old growth forest, biodiversity and the mycorrhizal network. Landfilled paper emitting methane gas. Overproduction of books … Timely interventions by writers Margaret Atwood, JK Rowling and Alice Munro, taking action not just with words but against their stock in trade: paper. In 2007 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows becoming the greenest book in publishing history. In the UK more than 15.74 millions trees saved annually if the industry only switched to post-consumer-waste paper …

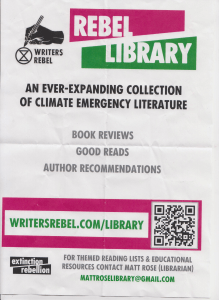

Then it was time for drinks, and I felt the need to move around, or maybe leave, so I investigated the basement for toilets, noticing an inspiring quote in the stairwell by Ali Smith on the way back up. Though knowing nothing about Swedenborg, I thought I might return here one day; I decided to stay and, back in the meeting room, approached the drinks table, the organisers channeling a soiree or a book launch. After taking in the scene, emboldened by the first sips of wine, I picked up a leaflet from a pile near an animated trio who immediately drew me into their conversation.

The creator of the leaflet was a Librarian from Powys who was compiling an ever-expanding list of climate emergency literature. His name and contact appeared at the bottom of the A4 sheet and I shared with him my impression that Climate Emergency did not have a shelf mark, that it was not a distinct classification: as Montaigne said, the subjects are all linked to one another. He agreed and offered to top up my glass. When he returned I leant into an evocation of Powys Public Library. His view was that Librarians are invisible except to those who can see them. He expanded, describing the assignations that sometimes took place in the building, readers assuming the person behind the counter was oblivious to their behaviour. In contrast there was one particular homeless man who wrote a poem every week and gifted him it. Every week. I wondered aloud if the street was his home, and maybe the Library an extension. I told him about the mathematician, then realising the second glass of wine had taken hold, folded the leaflet into quarters and placed it in my pocket, saying I looked forward to exploring the Rebel Library.

After the event I looked up the book Paper Trails, From Trees to Trash – the True Cost of Paper, now out of print. My British Library Readers card had expired just before lockdown and when I went to renew it, in March 2020, I didn’t have the right proof of identity and so left. In any case the library was fraught, the Assistant who dealt with me, brusque; another recoiled when someone in the queue coughed. Every evening there were the news images from Italian hospitals and everyone knew it was only a matter of time before the devastation reached us, yet the Government here acted as if they existed in an untouchable parallel universe. Now two years later I brought in the correct ID and ordered the book.

When I went to collect it a couple of days later, I noticed that several people had made the pavement in Midland Road, outside the Library, their home, though the tents were empty. I thought that in such a situation there was no choice but to trust fellow human beings not to steal your belongings while you saw to the business of the day. When the Assistant handed me the book in Humanities One, I was disappointed to see that it had no proper cover and was imperfectly bound, even for a paperback, cracking as soon as I opened the pages; by the time I finished the introduction, several of them had come loose. If ever a book should be made to last at least one reading, it must be this, but even though I tried to angle and not flatten the pages, I could feel the miserable object disintegrating. Was this an example of Books on demand publishing? The answer to overproduction? I left the building, rattled once more, and when I got home ordered a second hand copy online for 50p plus postage: ‘Ex library with usual stamps & stickers.’

Trail: 11

While I waited for the ex-library copy to arrive, I gathered my knowledge of paper technology, limited to a vaguely recalled diagram of an idealised paper making process used to practise the passive voice in an old-fashioned Language course, and an experience years ago when I taught English briefly in a paper factory in central Portugal. A taxi would collect me and before the factory came into view, the smell – a bit like decomposing barley – indicated its proximity. The class was held in a training room far from the factory floor and the attendees wanted to talk about anything but paper production. They liked reminiscing, though, and, when the narrative tenses were revised, wrote short texts, about the ritual burning of ribbons (Queima Das Fitas) in their college days, or leaving Angola when the Portuguese army withdrew. These recollections were written on small scraps of paper neatly torn from notebooks as if, producing paper, they had a code of honour not to waste it. I became fond of the foreman, Antonio, who showed me pictures of his boys and gave me a paperback book, Novos Contos da Montana, by Miguel Torga, stories set in the ‘remote and barren’ Tras-os-Montes, as a leaving gift. I remember his parting words. He addressed me by name and said: ‘You must make your decisions and not look back.’

Nearer home and the present, I considered the ratio: 25 books: one tree felled. Since working at the Library a massive and untypical book weeding project, long overdue, has taken place to catch up with changed times. I have now played a small part in the withdrawal of around 40,000 books, involving 1,600 trees (using the ratio). The Library Assistant’s role is to ease excess volumes from the tight shelves, utilising a spreadsheet created by the Librarian, which lists books that failed to be issued in however number of years and those rendered obsolete by more recent editions. Also, with digitisation the number of set books required for a module is much reduced.

The withdrawn books have been desensitised, stamped, and boxed up for the charity, Better Books, to donate and sell on. The books targeted for the weeding project were those John Feather, Professor of Library and Information Studies would describe as ‘dispensable’, with the proviso that information content was preserved somewhere. After all, the quality of service is measured by the speed with which a user’s demand is realised, the mission served, rather than numbers of books on shelves. In other words, these weren’t rare books or members of specialist research collections. Still, the Librarian sighed at their passing, but you have to make your decisions and not look back.

Post-script

The ex-library book has arrived; it’s a proper book with a cover design, a paperback that doesn’t crack and lose its pages and it’s printed on 100% recycled, good quality paper. I can’t do justice to its content. The global journey Haggith researched from tree to trash, which she undertook in 2006, starting from her home in Scotland, then overland to Sumatra and across North America, is a heart-breaking one, though told with humour and humanity. She lays bare the impacts of industrial paper production: the loss of forest habitats, abuse of human rights, contribution to global warming, pollution and waste, and identifies the agents of this destruction. She documents thoroughly a global regime of multi-national corporations that thrive at the expense of indebted southern countries The process could not be represented by a diagram practising the passive voice. If we are beyond fucked, we at least know who by with this book. But her parting message is more hopeful than that. It is not so difficult to reduce paper use, especially if we value it, every sheet of toilet paper, every page of every book.

For more information, visit http://www.shrinkpaper.org

Exhortations to slow down expansion, to plant fewer acres, … are of little avail as long as the motive is lacking. If it pays to waste we waste. When it pays to conserve we will conserve.”

Scoville Hamlin, The Menace of Overproduction, 1930

References

Feather, John (ed.), Managing Preservation for Libraries and Archives, Ashgate, 2004

Feather, John, The Information Society: a study of continuity and change, E-book, facet publishing, 2013. 6th edition.

Haggith, Mandy, Paper Trails, From Trees to Trash – the True Cost of Paper, Virgin Books, Random House, 2008

Hamlyn, Scoville, The Menace of Overproduction: Its Cause, Extent and Cure, Wiley, 1930