Death howl of dinosaur

Sometimes there is a place imagination holds so deep that it returns over and over to the lines it once drew, and the colours applied; it must dive down and complete this circuit no matter what. I think this was the case for the old man who came into the library recently, a calm Saturday afternoon. He had been sitting for some time in the corner by the large succulent near the entrance, before I noticed him rifling in an agitated way through a wheelie bag that reminded me of my mother’s buckled shopping trolley long gone. Eventually, thinking he might be looking for the badly signposted vaccination centre that occupies a temporary building on campus, I went over and asked if I could help at all. His eyes were dark and remote; his scalp was visible through thinning hair, and he had the slightly androgynous appearance of the very old. He paused for a long time and then sighed at being disturbed. I’ve come from Singapore, he said. I need to find the library. I studied here; I have the letter with me. Just give me a moment, please.

I returned to the desk and eyed him occasionally from behind the counter to see what he would do next. After a while when I had become absorbed in doing something else, he appeared, holding out the paper for examination. Still wondering what form of enquiry this was, I skimmed over the typewritten sheet which attested to him having been a student in the School of Engineering in 1975.

How can I help? I said. I need to find the library. For my memory, he explained. Looking steadily into his eyes I asked if there was anything in particular and he told me that unfortunately he had not completed his studies and had returned to his homeland, and then he received a communication about a book, an unreturned book, a book whose precise location on the shelf he remembered. An open space, a round space, with shelves, and steps. He was clearly mystified by the so-called library he had currently found himself in.

I checked with my colleague, (who had been a cinema manager previously and is surprised by nothing) if I could leave the desk for a few minutes and I walked round to the visitor. Come with me. I think I know where you mean. When we were outside, I asked if he was maybe remembering the Old Library. It was an open space, with books and shelves and steps he said again.

The former library was located in a listed building on campus, a part of the Victorian People’s Palace, and inspired by the Reading Room of the British Museum, with galleries and marble busts of famous men. Since its renovation in 2006 (which occasioned a scandal when skips of discarded books were discovered by students and academic staff), it has been used for such occasions as weddings, exams, and the BBC’s Question Time. The old books were replaced by more ‘authentic’ looking red leather-bound volumes. The original Library sign, embedded in the brickwork and also listed, still confuses visitors. (During the UCU strike a few years ago, the students occupied the space for a week or so and made, amidst the intimidating grandeur, a cosy home for themselves. For all the fakery it remains the symbolic heart of the campus.)

I’m afraid the Old Library is closed, I said, but I pointed up at the sign, which he peered at, nodding slightly, as if it made sense to him. He asked me if we were at the back of the building, and then seemed content to leave the matter there. Maybe he circumnavigated the building after I left him and put the library together in his mind. I’d like to think that a kind security guard may have let him in, but I doubt this. He may have been disappointed, but his pilgrimage was complete and he thanked me for my time.

* * *

I also harbour such places; most likely we all do. One that my imagination returns to is a place that I have never actually visited, and never can. I thought of it recently when I chose a withdrawn book to take home: History of the Earth, An Introduction to Historical Geology, by Bernhard Kummel, Harvard University, which presented for undergraduates the state of knowledge at its publication date, 1961. On the inside front and back covers are projections of the globe, the kind that look like flattened orange peel with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and Burma labelled.

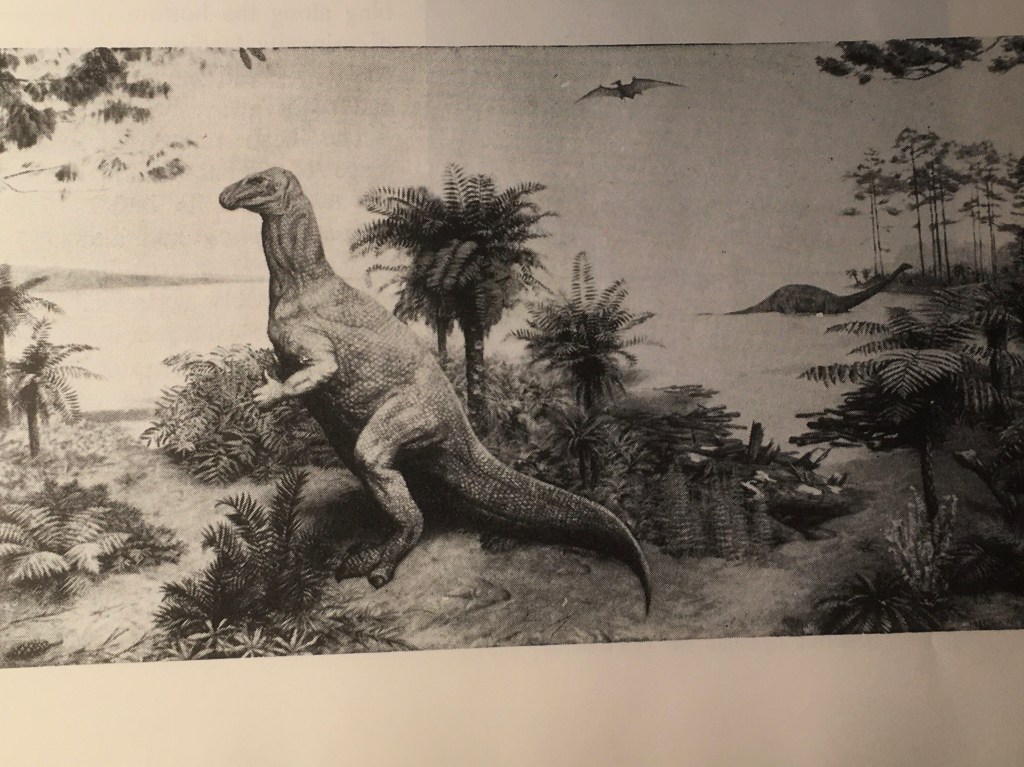

The shelf mark was reconsidered at one point and changed from a subdivision of Science (QE 501) to Geography (GBE 501). The book is date stamped steadily from 6 November 1963 to 7 December 1979 (when I guess manual issuing ceased) and the cloth cover smells of damp pavement. There are ample diagrams and maps, and the paper within is silky to touch. Courtesy of Her Majesty’s Geological Survey there are a few idealized landscapes of geologic eras, from the Pre-Cambrian to the Recent Pleistocene. The Anthropocene was yet to be coined. One period in particular, The Cretaceous, evokes the scene that my imagination frequents. According to the writer, this was a period of Geologic transgression where sea levels rose, shorelines moved toward higher ground and flooding ensued: as a consequence, our modern world was beginning to take shape.

The portal to this place of mine was the BBC Schools Broadcasting Service. On November 6, 1964, a class of nine year olds sat cross legged, or in a knee- hugging brace, on an institutional parquet floor, on the second floor of a Victorian school in East London, one that had a caretaker in a long black coat, a ghost, and base notes of dinners and disinfectant. Facing the group was a large box: a radio speaker, with a mesh-like entrance to the other world.

The voice from the box was authoritative, hypnotic and male and I suspect I missed the first half of the programme as I was settling in, but then it segued into another section, accompanied by music of a very different texture to anything I had heard before. Different to the singles stacked up on the living room radiogram in my nan’s council house which we shared at that time. As evocative as they were, in their white paper sleeves (with Nights Having a Thousand eyes), they were of this world, and the music from the box was of another. Then the man said: ‘I am standing on the shore …’ and gave an eye witness description of a lush prehistoric landscape where dinosaurs appeared on land and in the water and skies. I have a strong recollection of the colours, and the damp smell of the fern-like vegetation but like the engineering student of 1975, my memory consists of fragments: the spell-binding sounds, a gently spoken male voice uttering these words. It was as if the programme appeared from nowhere and then returned there.

When I embarked on my own quest to identify the basis of this memory, I was forced to accept that, many tides having visited that shore since, much of the historic BBC is a lost continent. The recording was not saved and all I was able to retrieve was a barely legible copy of the microfiched script, provided by a kind individual from the BBC Written Archives. Just as the former student had to settle for a mere sign that the Library had once existed, I had only this meagre record of the aural experience.

From this script I pieced together the programme, which was part of a series called How Things Began. This episode was Giant Reptiles Rule the Earth, by Henry Marshall, with an observer scene by Honor Wyatt. One of the consultants for the programme was the Professor of Zoology at Birkbeck, WS Bullough. The first half was a recap of the speaker’s previous visit to the Natural History Museum, but the eye-witness section continues:

I am standing on the shore by the mouth of a wide river. All around me ... are creatures that look like dragons. ... In the water monstrous shapes only partly seen. In the air the silent flight of bat-like wings circling overhead, narrow scaly heads with bright unblinking eyes looking down at me. Landwards on the crest of a little hill, a huge monster is staring towards the horizon - staring without movement, as still as a carved thing, terrible in its hugeness - lord of the earth!

The land-based creature is an Iguanodon, a plant eater with dagger-like claws, and I can’t help but notice that the scene closely resembles the illustration in the obsolete geology text book now in my possession. But then the tableaux takes a dramatic turn. Forced to leave the shore by the arrival of swooping flying reptiles with 20-foot wing spans, the narrator moves to a nearby wood where he watches this ‘queer world’ as if standing outside it looking in. Nearby where he is standing in the woods, he spots a small creature that looks like a rat, but covered in fur, frightened-looking but still, cowering among the tree roots. Then he notices a little cluster of eggs just behind it. Tiny squealing noises are indicated and ‘one of the eggs is cracking’.

What he witnesses next is the water-based reptile with lashing tail attacking the Iguanodon, both so huge that they seem to ‘fill the whole world’. The flesh eater wins. The Iguanadon is brought down: (FINAL DEATH HOWL OF DINOSAUR – LONG DRAWN OUT, THEN PAUSE).

The episode concludes with the demise of the giant reptiles, the focus now on the birds possessing the sky, the fish the sea, ‘the tiny furry mammals’ the land, and the observer asks: ‘What would they make of it?’

* * *

The past changes from year to year, and with every descent. In my excavation of this period of BBC radio broadcasting, I discovered that the series was exceptional in several ways, aside from having the ability to create awe in a nine-year-old child. One was its approach to evolution, the series, How Things Began (HTB) having itself evolved from the first radio treatment of evolution, a series of short lectures in the mid 1920s called The Stream of Life, by the evolutionary biologist, Julian Huxley.

An important departure from the didactic lecture format was the use of drama in science broadcasting, the influence of the playwright Nesta Pain, who joined the BBC in 1942, (after separating from her husband in Liverpool and moving to wartime London with her fifteen year old daughter). A further contributor to this dramatic turn was a progressive author and broadcaster Rhoda Power who joined The BBC Schools Broadcasting service permanently in 1939. What she brought to it was an experimental approach, bringing radio broadcasts to life with the use of sound effects, period music, dialogue, and dramatisations of historical events. The writer of HTB’s ‘observer’ section, Honor Wyatt was a journalist and radio presenter (mother of musician Robert Wyatt) who had been friends with a group that included Robert Graves.

During the Second World War, Wyatt worked for The BBC in Bristol as a writer for the Schools service. What she had at her disposal when HTB was produced, was The BBC Radiophonic Workshop, set up in 1957 by the trained musician Daphne Oram with Studio Manager, Desmond Briscoe, in Maida Vale. Using magnetic tape, razor blades and found objects, this pioneer of analogue electronic music created sounds that no-one had heard before, something she did by stretching, overlaying and altering the speed of tapes. She had left the Maida Vale Studio, by the time HTB was produced, to work on her own machine, Oramics, which enabled her to control sound through snake-like drawings on glass. In this way Oram was imbuing electronic wave forms with the human qualities she considered were missing. But she had released her creative spirit into the world, and it reverberated as far as my classroom in 1964.

These induced resonances in all wavebands remain with us, if renewed by memory and repeated experiences, so that eventually they become frequencies in our own personal wave pattern.

Daphne Oram, An Indvidual Note, Anomie Publishing, 2016

Other Reading

Alexander Hall, Evolution on British Television and Radio, 2021

With thanks to Emma Holding from The BBC Written Archives.