Fragile History

… we need to bring the classroom and the academy into the library, thinking more about playground and less about sanctuary.

Jim Neal, former President of American Library Association

TuktuktuktuktukteteteteteBAAH Hubbubhubhubhubhub

The sound of the red and green alarms, the inflow and exit of users, mostly undergraduates, groups of brothers, loud affirmations, serious girls, and not, sometimes researchers and academics returning bags of books that have reached the limit of automatic renewal, some lone readers like the mathematician who come and go unobtrusively. It could be the tube or an airport but for the clapping, shouting, laughing. Excuse me excuse me, meaning Stop, when a Library Assistant has spotted a KFC bag, or an attempt to bundle in a friend who doesn’t belong. The electronic sentinels still not fully functioning after their long covid sleep, giving messages that are all awry: it’s saying I am unknown, it’s saying I am in when I’m out. Scan the barcode scan the barcode.

Once the threshold is crossed and the barcode acknowledged, behind glass walls is the Group Study Area, and here there are elements of a playground if this is what the former ALA President had in mind. This is down to the space, as long as a sprint track, and the chairs which have irresistible wheels; the library, too, is one of the few places where you can hang out without spending money. For the most part the library never closes and maybe that is a type of refuge. Group projects are commonplace and not everyone is a solitary scholar by nature. Some of the group study areas hum with concentration but the main room is often noisy, disarrayed, apparently how the users like it.

As Andrew Pettigrew and Arthur der Weduwen, the authors of The Library A Fragile History write, libraries need to adapt to survive, and today’s University libraries are, generally speaking, as much social spaces as sanctuaries. What the authors of this immense study of the fragility of libraries document is what they consider the historical norm: ‘ a repeating cycle of creation and dispersal, decay and reconstruction.’ This they do, from the library of Alexandria, to the French renewal of dilapidated public libraries, in the form of Médiathèques. A powerful UK example offered concerns the University of Oxford which, in 1556, its book stock ruined, sold off the Library furniture only for the institution to rise again fifty years later with the establishment of what was to become the Bodleian Library.

The key accelerator for the current cycle being enacted in the library is shortage of space, and the adaptations most in evidence concern digitisation and the giving over of space to readers in response to consumer demand. This has involved a financial investment that needs to be capitalized primarily in terms of growth in student numbers and so the wheel turns.

Leaving the bookless expanse of group study, stairs lead to the silent Reading Rooms, the stacks unlit until a reader appears, the carrel-like tables beside the wide windows, rows of heads bent over laptops, with the accoutrements of study: earbuds, crisp packets, coffee cups but please note no hot food. Here space is a constant concern, all books having to pay their way. But how is this determined?

In May 1947, Charles F. Gosnell of the New York State Library, published his response to the question in an article entitled ‘Obsolete Library Books’. I imagine Gosnell intoning his words: ‘Books are born, they grow old, and die, certainly as far as our interest in them is concerned’. A page later he continues, ‘The causes of book mortality or obsolescence are many, varying from pure fad through extension of scientific knowledge and technological advances to fundamental changes in our civilisation.’ He emerges eventually with complex formulae for establishing a satisfactory demographic among the books, but all the care he took now seems redundant, as library policy today is simply to buy the e-book wherever available, technological advances and fundamental changes, including the pandemic, having decided the matter.

And so Circulation Managers may dream of the end of the actual book, but, Not so fast, Pettigrew and der Weduwen counsel, citing the futurologist Richard Watson who reversed his initial prediction that libraries would go virtual and librarians be replaced by algorithms. The reason: ‘Libraries are slow-thinking places away from the hustle and bustle of everyday life.’ Would they be places of deep reading without books? James M Donovan, a Law Librarian, meditates on this question, arguing that universal digital access would entail ‘informational homogeneity’ and an ‘antithesis of the value of particularity embodied in the library’. In other words, libraries are more than aggregates of books, because each collection has history and its physicality holds traces of a time and culture. In another article he takes this further, conducting a study on the impact of books even solely as backcloth or ‘wallpaper’ and concluding that, supposing all books were in reality replaced by digital resources, the space that remained would not be a ‘library’. The changes would leave the reader with a degraded environment in which to comprehend ‘content’.

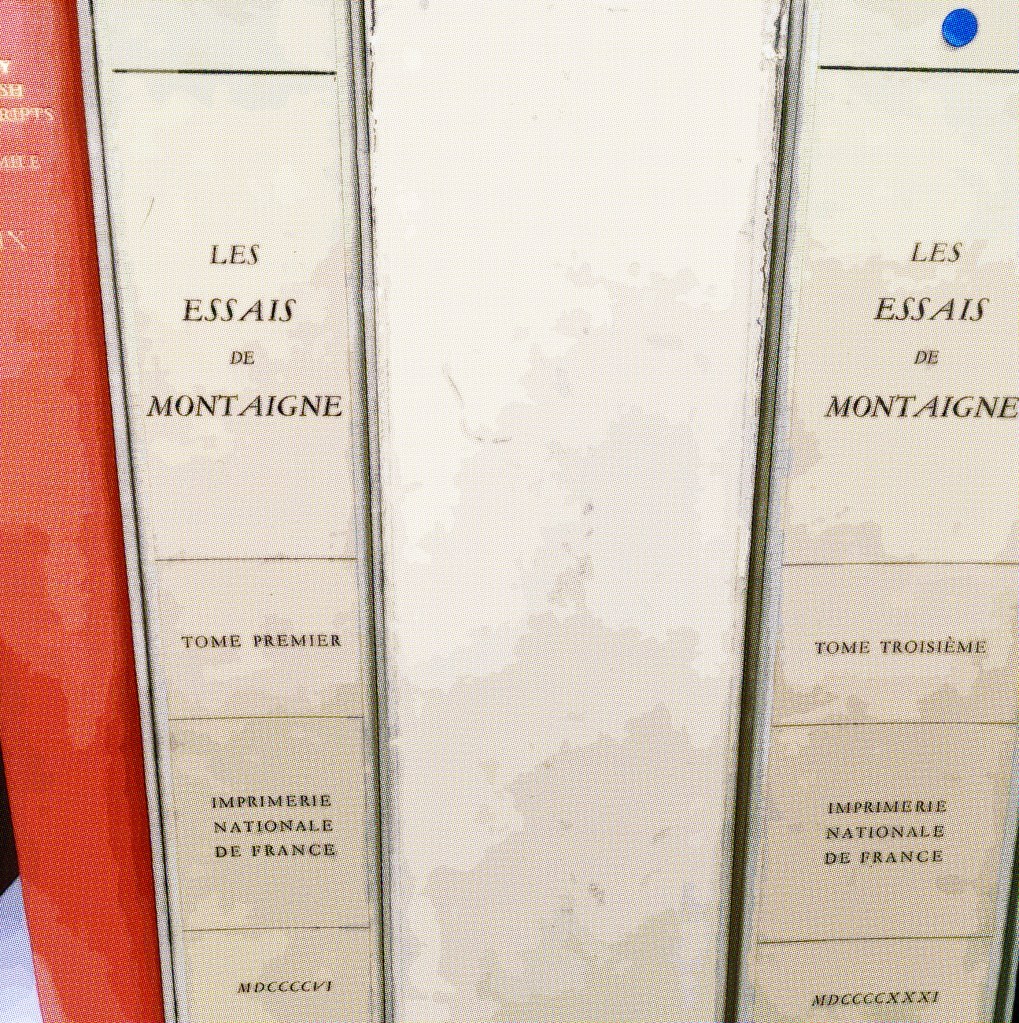

This is known. The essayist Michel de Montaigne was famously influenced by the library he wrote in, a tower with over 1,000 books. Ray Bradbury, who learned to be a writer in his hometown library, describes the way that books need to be sensed by smell, look and touch: only then can the reading process be contemplated. In a piece written for National Library Week the writer described the moment of reaching the Carnegie Library as a child:

And there was always that special moment when, at the big doors, you paused before you opened them and went in among all those lives, in among all those whispers of old voices so high and so quiet it would take a dog, trotting between the stacks to hear them.

Ray Bradbury, Monday Night in Green Town

We should not neglect the body: I still recall the Foundation student who said, when asked about her reading, ‘I need to hug the book.’ What is required to embrace learning is still not fully understood. What I feel about the library is what the Surrealists understood: the power of assemblage, the value that randomness adds. I wonder what type of market research a Surrealist would conduct. It would certainly not involve, What do you want? but, maybe, What is a book, a Library, a group, study itself?

Every subject is equally fertile to me: a fly will serve the purpose … I nay begin with that which pleases me best, for the subjects are all linked to one another

Michel de Montaigne, Essays, Volume Three

References

Donovan, James M., Keep the books on the shelves: Library space as intrinsic facilitator of the reading experience, The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46, 2020

Donovan, James M. Libraries as Doppelgängers: A Meditation on Collection Development, from the Selected Works of James M. Donovan, University of Kentucky, Winter 2009

Eller, Jonathan R., Becoming Ray Bradbury, University of Illinois Press, 2011

Gosnell, Charles F., Obsolete Library Books, The Scientific Monthly, May 1947, Vol. 64, No. 5

Montaigne, Michel de, (1553-1592) Essays, (electronic resource), Translated by Charles Cotton, 2001

Pettegree, Andrew & Der Weduwen, Arthur, The Library A Fragile History, Profile, London, 2021