The Mathematician

Mathematicians speak of the beauty of their subject, something I can appreciate only obliquely because of lack of understanding. There is a beauty to the language of mathematics I realised during a period in the library when the sorting system was out of action, and returned books had to be manually checked for holds. Opening a returned graduate maths book at random one day, I noticed the writers had prefaced their text with a quote from TS Eliot’s Four Quartets:

The end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Flicking through, I landed on a random paragraph, which posed a question concerning the limit to a family of ideals and contained the words: polynomial and infinite co-dimension. I wondered about this family and what its limits may be.

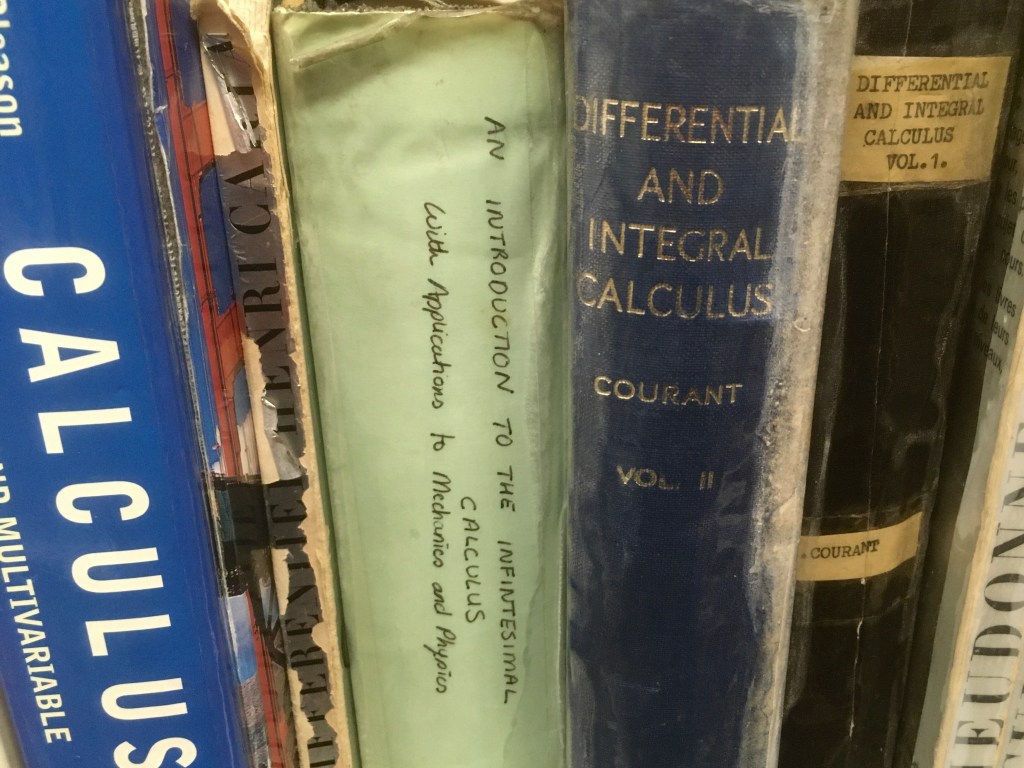

Recently, a mathematician approached the Library Welcome Desk. Unlike many students, he hadn’t fixed on any particular look; he wore a plain hoodie and his hair was unstyled, although heading for an afro if given license. He looked like he was still at school and, eyes lowered, came out with it straight away: I can’t find a book. I need this book. I asked if he had checked the catalogue and he said: It’s daunting, finding a book with all these books. That’s the word he used. I went with him to the OPAC terminal and he keyed in his title, a text on calculus, which came up pretty quickly; I scrawled the shelfmark on a piece of scrap paper, using one of the small child-size pencils kept in a tray. I was surprised that the book was published in 1975, but assumed that this was the timeless beauty of mathematics. He had no idea where to begin to find the object of his quest.

Together we took the stairs to the First Floor Reading Room and halfway up, I asked if this was his first year. Second, he said. Lockdown was the first year.

Teaching during lockdown, I was aware of various phases. In the emergency phase of March, 2020 the group I was working with was small and at an independent stage of their module. In the first weeks, attendance was erratic as all the international students who could get out, did so. They dropped in and out of calls and struggled with broadband and were bemused at first to talk to me through a screen. Regrouped according to time zones, we were together, still, and once they were transplanted in their new locations, returned to cats and family decors, and I had views of snowy scenes and stray family members, or luxuriant tropical gardens, we settled into a routine. I used my hour of exercise learning to run again and put up prayer flags a friend had brought back from Nepal in a tree in my locale. A few students who couldn’t get flights out were worryingly isolated. As the months went by, I watched the prayer flags bleach.

The mathematician would have started his degree in the October of that year, when, in the middle of the new normal, the modules had all been migrated and students had settled into whatever patterns suited them. I wondered what it would be like to study maths online, whether his books were digitised; maths students often praise the certainties of their subject. Maybe this made it easier. Could that be true?

Most of my new group of home students at that time were muted and unseen. I had all the tools of Teams, mentimeter, video sharing apps. We were reminded to look after our mental health and there was some talk of the affordances of the situation, of exciting opportunities. After some months, I left teaching.

Now in the Reading Room, we wove in and out of the shelves, scanning. sometimes in shadow as we waited for the light sensors to engage. We were in data science, before the confluence with classical mathematics. The data science spines were uniformly silver and the class marks fiendishly complex. Before the bulbs in the stack were triggered, the space appeared like a shimmering tunnel leading to the light of the reading room. When data eventually met mathematics, this uniformity changed, each volume now possessing a distinct personality. This was partly the work of the Collection Care team tenderly effecting their repairs. We were getting closer. It’s there, the mathematician said. He plucked the book from between two weightier ones and a smile released his face.

In the following weeks as I tried to inform myself of the basic functions of calculus, I wondered how the mathematician estimated his own progress during that period. I doubted an exact rate of change at one precise moment would be calculable. There would be slopes, though: the rise over run. I thought of a time many years before the pandemic when, precariously employed by the Humanities Department of a university where the attachment of mathematicians for chalk was accommodated, I would sometimes find myself in a classroom previously used by such a scholar. When that happened, I would study the unreadable constellation of symbols for a moment before erasing them, then wait for the chalkdust to disperse and begin again.

calculus noun

an area of advanced mathematics in which continuously changing values are studied

Cambridge Dictionary